18.11.22

5.11.22

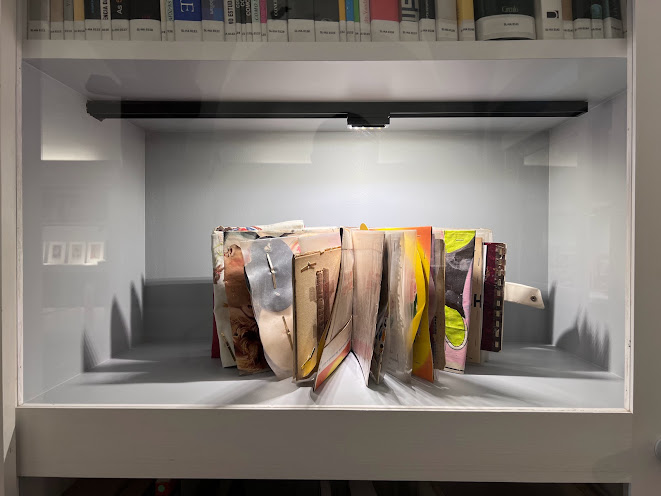

Folha de Sala - não me peça que lhe dê pormenores” - Gabinete de Leitura - Casa da Cerca

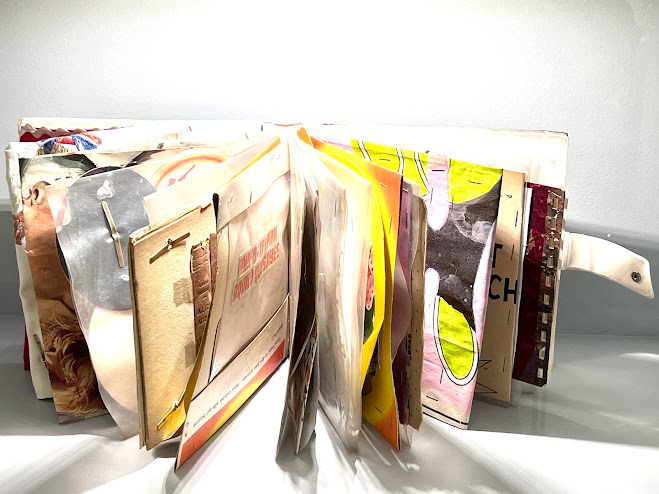

Desde os anos 80, ainda a frequentar a Escola de Belas Artes de Lisboa, que Ana Vidigal faz livros de artista. O último que apresenta na exposição é datado já deste ano, 2022. Não são livros de projetos, ou de esboços, nem são livros de ideias. São obras. Cada uma deles dá continuidade ao trabalho que a pintora realiza nas suas telas, desenhos ou instalações, seja pela sua estética, temática ou apenas pela técnica. Por vezes, nascem de um projeto específico para o formato livro, outras advêm da vontade de guardar material, ou restos utilizados noutras obras e que nos aqui ganham uma nova dimensão. Se na pintura trabalha por séries, Vidigal aborda cada livro como um projeto isolado (com algumas excepções), mas no qual trabalha ao longo do tempo.

Ana Vidigal afirma que nunca começa uma tela em branco, o mesmo acontece com os seus livros. A colagem é aqui, como em grande parte da sua obra,uma das suas técnicas de eleição. O seu processo artístico – igual há mais de 40 anos - passa por uma recolha obsessiva de material que guarda em caixas: espólios de família, heranças de amigos, encontros em feiras de segunda mão - postais, fotografias, revistas, moldes de costura, novelas. Antes de começar umapeça ou série, volta aos seus caixotes, ao seu arquivo. Aescolha de que material utilizar é sempre intuitiva,emotiva e também situada num determinado contexto da sua vida e do mundo.

Marcada pelo humor e ironia, a obra de Ana Vidigal é também altamente politizada e crítica. A aparente simplicidade e proximidade dos materiais que escolhe – fotografias domésticas, bandas desenhada, lavores, -marcados por uma imagética infantil, algo pueril e popular, permitem que a artista aborde de forma subtiltemas fraturantes da sociedade portuguesa como o papel que é atribuído à mulher, o racismo, a questão colonial. Muito do material que usa/acumula carrega mensagens subjacentes com um cariz patriarcal, machista, racista e fascista, o qual Vidigal tenta denunciar e expor. Vejamos o exemplo de um dos livros de artista que apresenta na exposição. A Guerra Colonial tem sido também um tema importante no seu trabalho. Define-se como filha da guerra, e as suas consequências continuam a deixar marcas profundasem si e na sociedade. Numa das suas caixas de arquivo encontrou um conjunto grande de postais fotográficos trazidos pelo seu bisavô, . para tentar mostrar à família o que viveu e o que encontrou, enquanto esteve estacionado em África durante as guerras da libertação. Vidigal legendou cada imagem com provérbios, provenientes de uma pesquisa à palavra ‘negro’ que aartista realizou no livro de ditados portugueses. Deparou-se com ditados de uma enorme violência racial, que ainda hoje continuamos a proferir sem nos apercebermos muitas vezes do profundo racismo que carregam. Se, por um lado, a conjugação dos provérbios com as imagens descontextualiza e reconfigura-as, por outro lado, Vidigal aponta o dedo as estruturas racistas que continuam a marcar o nosso quotidiano e identidade, baralhando, densificando e problematizando as imagens que consumimos acriticamente.

Ana Vidigal has been making artist's books since the 1980s, when she was still attending the Lisbon School of Fine Arts. The last one she presents at the exhibition is from this year, 2022. They are not books of projects, or sketches, nor are they books of ideas. They are works. Each one of them gives continuity to the work the painter does on her canvases, drawings or installations, whether for its aesthetics, theme or just technique. Sometimes they are born from a specific project for the book format, others come from the will to save material, or leftovers used in other works and that here gain a new dimension. If in painting she works in series, Vidigal approaches each book as an isolated project (with some exceptions), but on which she works over time.

Ana Vidigal states that she never starts on blank canvas, the same happens with her books. Collage is here, as in much of her work, one of her techniques of choice. Her artistic process - the same for over 40 years - involves an obsessive collection of material that she keeps in boxes: family heirlooms, friends' inheritances, encounters at second-hand fairs - postcards, photographs, magazines, sewing patterns, novels. Before starting a piece or series, she goes back to her boxes, to her archive. The choice of which material to use is always intuitive, emotional and also situated in a certain context of her life and the world.

Marked by humour and irony, Ana Vidigal's work is also highly politicised and critical. The apparent simplicity and proximity of the materials she chooses - domestic photographs, comic strips, lavender, - marked by a childish, somewhat puerile and popular imagery, allow the artist to subtly address fracturing themes of Portuguese society, such as the role attributed to women, racism and the colonial question. Much of the material she uses/accumulates carries underlying messages of a patriarchal, macho, racist and fascist nature, which Vidigal tries to denounce and expose. Let us look at the example of one of the artist's books presented in the exhibition. The Colonial War has also been an important theme in her work. She defines herself as a child of war, and its consequences continue to leave deep marks in her and in society. In one of her archive boxes she found a large set of photographic postcards brought by her great-grandfather, . to try to show her family what she experienced and what she encountered while she was stationed in Africa during the liberation wars. Vidigal captioned each image with proverbs, coming from a research on the word 'negro' that the artist carried out in the book of Portuguese sayings. She came across sayings of enormous racial violence, which we still say today without often realising the deep racism they carry. If, on the one hand, the conjugation of the proverbs with the images decontextualises and reconfigures them, on the other hand Vidigal points the finger at the racist structures that continue to mark our daily life and identity, shuffling, densifying and problematising the images we uncritically consume.